Celebrating Four Decades of Advocacy

Celebrating Four Decades of Advocacy

This year has been a notable one for our union. Not just because of the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, the opioid crisis or the heatwaves that have gripped the province – although the leadership that nurses have shown in the face of these crises has been remarkable – it's because 2021 marks the 40th anniversary of BCNU's inception, when a group of nurses gathered in the ballroom of the Empress Hotel in Victoria, and took the final steps to becoming an independent union, separate from our professional association.

There is a famous proverb that aptly describes BCNU's journey to date: If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. As BCNU celebrates its 40th year, and as we look back over the past four decades, there is no question that BCNU members have come far, and it's because we've travelled together. We've helped ourselves by helping each other. This is the essence of solidarity and collective bargaining. We are stronger together.

We can also be proud of the difference we have made in the lives of our patients, and of the advocacy work that our union has done on behalf of our communities. We are a powerful force for good.

Uniting BC's nurses in service of this mission is what BCNU's story is all about. Across professional designations and across sectors, nurses in BC are united today in a way they have never been before.

BCNU has changed significantly since that historic first convention. We've grown in size from 16,000 to more than 48,000 members. We've evolved from a relatively conservative organization that emerged from the Registered Nurses' Association of BC to become a member-driven union. For example, BCNU's elected president didn't become a full-time paid officer until the late 1980s. Until then, most public outreach, including lobbying the government and speaking to the media, was done by paid staff members.

Today, we're a more democratic and open union, with our president and executive committee members elected by all 48,000 members instead of by several hundred convention delegates. In the past 40 years we've transformed ourselves from an organization focused mainly on negotiating contracts, handling grievances and other labour relations issues into one that champions a wide variety of social justice issues, becoming one of our country's most respected and outspoken defenders of public health care.

Nurses have seen considerable improvements in wages, benefits and working conditions. And we've now brought nearly all publicly employed nurses under one provincial collective agreement, which has allowed us to level wages and benefits between sectors considerably, with long-term care nurses earning the same as their acute care counterparts.

BCNU has also become a member-centric organization that's empowering nurses to enforce their contract and stand up for rights in their workplace. We've made great strides promoting human rights and social justice, and are becoming an inclusive and culturally safe organization that embraces and promotes diversity and equity.

BEFORE BCNU

Improving the lives of working nurses began long before BCNU's first historic convention. But without a union advocating on nurses' behalf, progress was slow.

The Registered Nurses' Association of BC (RNABC) resisted calls from members to begin collective bargaining for nurses around the province until 1946, when Vancouver General Hospital nurses voted to join the Hospital Employees Federal Union (now HEU). After RNABC reversed its decision, St. Paul's Hospital became its first certification, followed by several other Lower Mainland facilities.

BCNU's founding was hastened by a landmark 1973 Supreme Court of Canada decision. The court ruled that the board of the Saskatchewan Registered Nurses' Association could be unduly dominated and influenced by management nurses and therefore shouldn't also be the nurses' bargaining agent. That judgment soon led to the formation of the Saskatchewan Union of Nurses and other Canadian nursing unions.

In 1976, the RNABC Labour Relations Division (LRD) was formally established to bargain for nurses. The LRD had its own elected governing body, separate staff and funding. The RNABC and its LRD formed a joint committee to study the issue of separation in 1980. It unanimously recommended the two bodies separate completely.

"We were able to make a huge difference in their standard of living and working conditions."

- Debra McPherson

In February 1981, the division held a special founding convention. The vote to become BCNU was a foregone conclusion, and it passed unanimously.

In 1983, BCNU negotiated its first Master Collective Agreement. It provided marked improvements in rights and benefits, mostly covering nurses working in acute care facilities. Throughout the 1980s, the number of members and facilities covered by the agreement continued to increase.

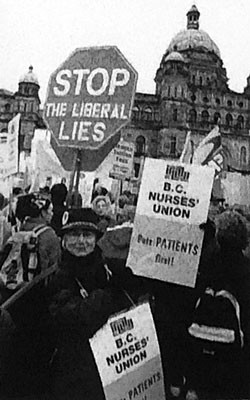

Also in 1983, BCNU participated in a province-wide firestorm of protests against Premier Bill Bennett's draconian "restraint" program. A coalition of unions, including BCNU, and community groups launched Operation Solidarity to fight the legislation, which included: elimination of human rights protections and the drastic curtailing of public sector collective bargaining rights.

BCNU president Wilma Buckley was a keynote speaker when nurses joined 20,000 other protestors on the lawn of the legislature. "The provincial government has launched an attack on citizens – subverting rights, destroying vital services, putting British Columbians second to an anti-social philosophy," she told the crowd. "That is intolerable. Nurses are for putting an end to it. This is why we are here today, to fight for people."

ORGANIZING IN LONG-TERM CARE

In the early 1980s, BCNU launched a campaign to organize nurses working at non-union long-term care facilities. That long campaign was the first step in a process that put BCNU on the map as a union at the forefront of the struggle for social justice for all. BCNU's goal was to bring the wages, benefits and working conditions of underpaid and unorganized nurses up to the same standards as their hospital colleagues.

Debra McPherson is BCNU's longest-serving president. She first served from 1990 to 1994 and again from 2001 to 2014. Prior to leading the union, McPherson was active on her Vancouver regional executive and attended the union's inaugural 1981 convention.

She clearly recalls the conditions in the long-term care sector in those days.

"There was a huge disparity of wages and working conditions between community, acute care and long-term care. They were vastly different and generally long-term care and community nurses were underpaid and undervalued. But for all nurses at that time the wages were not good; they were low," she says.

"BCNU was pretty much legislated to be the rep for acute care nurses but not for those in long-term care," she explains. "So we were busy organizing in the 80s under the guidance of Ray Haynes, who was a labour relations officer at the time."

McPherson says organizing the worksites was difficult, and those nurses who adopted the union and signed cards were very courageous and did so at great personal risk.

Many employers used intimidation tactics and, occasionally, tried to fire the nurses. Organizers worked very clandestinely, meeting in people's homes until they knew a positive vote had been cinched.

"We had to organize those worksites one at a time from the ground up – and that was hard," McPherson recalls. "Because there were and continue to be ghettoes of racialized nurses subject to low pay, poor working conditions and serious employer harassment and intimidation.

"But by organizing them, we were able to make a huge difference in their standard of living and working conditions."

One of the first victories came in 1982, when a strike at Carlton Private Hospital resulted in nurses receiving wage parity with hospital nurses. As news of their successes spread, non-union long-term care nurses around the province began contacting BCNU, and the union eventually organized 1,000 nurses in over 100 facilities.

"I saw other staff being treated unfairly. That really bothered me."

- Deb Ducharme

In 1985, nurses launched job action at 12 private long-term care facilities and stayed off the job for up to 20 days. In 1987, nurses at 16 private facilities, took job action, lasting up to 41 days.

Salmon Arm's Deb Ducharme is no stranger to organizing. She served as BCNU's executive councillor for pensions from 2010 until her retirement in 2017. Prior to this she served members in a variety of union positions, including regional treasurer and Thompson North Okanagan region council member.

Ducharme has been a life-long union activist. "I was raised in a union household," she explains. "My dad was extremely active in the United Transportation Union [which represents rail workers] and served as a president throughout my teens. I grew up discussing union issues with my parents."

Ducharme put that knowledge about unions to good use early in her nursing career. After graduating as an LPN at 19, she landed her first job at 100 Mile House Hospital, which at the time was a non-union facility. But it wasn't long before the teenager helped her co-workers launch an organizing drive that ended with a first union contract.

Several years later, shortly after becoming an RN, Ducharme moved to Salmon Arm and began working at Bastion Place. "It was a new, non-union facility," she recalls. "I felt very uncomfortable because I saw other staff being treated unfairly. That really bothered me, because one of my basic beliefs is that everyone should be treated fairly and equally. So, I began working with two other nurses to organize the facility."

Full victory for most long-term care nurses was finally attained in 1991, when an arbitrated settlement resulted in wage parity, plus health and welfare benefits equal to those of hospital nurses.

THE STRIKE OF 1989

The tumultuous 1989 strike played a defining role in the future development of our union. Negotiations for a new contract opened in February, with nurses demanding a 33 percent wage increase and other contract improvements to help resolve workplace practice and safety issues.

Employers responded by submitting a long list of concessions, including reductions in sick leave and other benefits.

BCNU launched a series of TV ads aimed at raising public awareness about the growing nursing shortage and the threat it posed to patients. "BC nurses have been undervalued for years," BCNU president Pat Savage told the media, "and we believe our time has come."

In May, nurses voted 94 percent in favour of job action, which began with a ban on non-nursing duties. That tactic quickly led to the appointment of a mediator. Over the next several weeks, numerous issues were resolved, including 30 weeks' maternity leave, provisions affecting portability and improved casual language.

The following month, employers finally submitted a three-year wage package with increases of 5.5, 6 and 6.5 percent. BCNU's counteroffer was refused and the employer declared further discussions pointless.

Within days, BCNU members launched a province-wide overtime ban and withdrew all but essential nursing services from 12 hospitals. Days later, 69 facilities were behind picket lines.

After a week of intensive mediation, a tentative settlement was reached and recommended by both the employer and BCNU's bargaining team. The three-year package called for pay raises of 29.5 percent.

But a large and vocal group of nurses were extremely unhappy with the deal and the lack of bargaining information coming from the union office. Soon, more than 700 angry nurses packed into Vancouver's Plaza 500 Hotel to demand answers about the contract from BCNU's staff and elected officials.

"Our president, Pat Savage, came by herself," recalls McPherson, who was a BCNU council member at the time. "No one from the bargaining team or senior staff accompanied her. It took courage for her to stand up to the members and answer all their questions.

"One lesson we learned in 1989 is recognizing the fact that that during job action it's the members who drive the engine, and the leaders have to stay in touch with them and keep them informed."

Some 150 irate nurses held a rally outside BCNU's office. Some of them occupied the building and held a news conference, demanding negotiations for a better contract resume immediately.

In the following days, many Vancouver-area nurses donated money for a "Vote No" campaign, which was led by McPherson and fellow council member Bernadette Stringer. The pair traveled the province by car, meeting with nurses, listening to their concerns and urging them to reject the proposed package.

On July 12, 65 percent of nurses voted against ratification, with members in eight of BCNU's nine regions voting to reject the deal.

Mediator Vince Ready soon entered the fray and, on August 18, announced a series of binding recommendations. The new contract was for two years instead of three and raised wages by 20.9 pe cent; from $17.43 per hour to $21.08, the highest in Canada.

"We accept the report under duress," BCNU President Pat Savage declared at a news conference at the end of the bitter six-month struggle. "We will begin now to prepare for the next round of negotiations – and to develop mechanisms to make sure the public understands the patient care problems that are sure to result from this shortsighted settlement."

McPherson says the 1989 dispute revealed a fundamental division in our union. One that was between those who wanted to lead from the top and those who wanted to lead from the bottom. "When we came out of that strike our little rump caucus decided that we really wanted to make change and to run to be the leadership of the union," she says. "I won the coin toss on that one, and so I got put forward as a candidate to be president. I ran and won."

McPherson served two two-year terms between 1990 and 1994 – when there were term limits – and remembers that effecting change was not easy. "There was huge resistance. The staff were used to being in charge and telling people what to do," she says. "They didn't want to be involved in the democratization of our union. So there was huge staff turnover during those four years and certainly building trust was hard.

"And we had resistance from the more conservative elements of the membership, particularly past leadership – just turning the boat a little bit was really difficult at that time."

UNITING COMMUNITY NURSES

BCNU's first decade of bargaining for hospital nurses set the stage for expanded organizing in the 1990s.

In 1990 public service nurses directly employed by the provincial government launched a strike to achieve parity with hospital RNs. They walked picket lines, handed out leaflets and met with their MLAs and the media. After five weeks of job action, they won a 22 percent wage increase, bringing them nearly in line with hospital nurses.

McPherson says it was a time that was full of possibilities.

"There was the provincial public service agreement and then each municipality in the lower mainland had its own community agreement," she explains.

"Bringing those community nurses into our union was important."

- Linda Pipe

"So first we had to bunch all those up and then we had to bring together the public service and the rest of the communities into one contract.

"It was a really exciting trying to achieve contract parity and our push toward one master agreement meant we were uniting a lot of RN groups along the way," she says.

Linda Pipe knows a thing or two about uniting nurses.

One of BCNU's longest serving leaders, she was the union's Fraser Valley region council member from 2003 to 2014. Prior to this, she served members as her region's OHS rep in addition to her steward duties.

Pipe began her 40-year nursing career at Mission Memorial Hospital in 1980 and worked in a variety of areas during 30-plus years on the job, from the ICU and ER to med-surg and extended care.

Like many other BCNU activists, Pipe became a steward during the tumultuous days of the strike of 1989. "It was a real watershed moment in BCNU history," she says. "Until then, I don't think nurses were taken seriously by politicians and employers. But by speaking out and taking a stand we really showed the strength that nurses have when we are united."

She says that building relationships with community nurses was a challenge in the 1990s because many didn't trust that the union would listen to their concerns, versus those of acute care nurses, who were in the majority.

"Some community nurses had a feeling that they were not heard by BCNU and so one of my goals was to make them feel that they were a valued member of the team."

Pipe says the fact that the Fraser Valley region had the largest number of community nurses in the province meant bringing them into the fold as active BCNU members was especially important.

"Their membership was very positive for this region and brought a whole different perspective to our regional meetings," she recalls.

But there were bumps along the way.

"Nursing was starting to specialize more, and to be a community nurses you had to have your degree. So there was a little bit of condescension about the fact that they had a degree and that most acute care nurses had our diploma," she reports.

"When I was regional chair I tried to get people to see that, yes, some of us had more learning but others should be just as valued for what they bring to the nursing team," she says. "And it was the same with [organizing] LPNs. They have their values as well. But nobody is better than the other, we just have different scopes of practice."

TACKLING WORKLOAD AND STAFFING

The changes to health-care management and delivery in the 1990s saw the union make staffing and workload one of the top items on the bargaining agenda.

Ask any nurse who has been working for more than 30 years and they'll tell you about a time when they exercised greater professional autonomy and control over their practice. And they'll likely recall a time when they experienced greater job satisfaction and positive patient outcomes, despite the inferior wages and benefits they once received.

Clinical nurse autonomy and control over nursing practice is part and parcel of the responsibility nurses have to act according to their own judgment and provide nursing care within their full scope of practice. But changes in health-care delivery over the last three decades have eroded nursing autonomy while dramatically increasing nurses' workloads.

Since the 1990s, nurses have been dealing with a health-care restructuring model based on such concepts as "lean" production and "total quality management," with nursing work perpetually measured by managers and becoming increasingly fragmented.

Nursing leadership has also been attacked over this time, as program managers with large spans of control and little knowledge of nursing practice now exercise greater control and decision-making ability.

Combined with budget cuts and the imperative to do "more with less," this restructuring has resulted in heavier nurse workloads and loss of job satisfaction.

Workload is now an abiding concern for the union, and BCNU has had significant success addressing the issue at the bargaining table. But all too often, the mechanisms negotiated to deal with workload have often been difficult and time consuming to implement.

Health employers in BC have been resistant to share decision-making power and involve nurses when making decisions about resource allocation and staffing, even though it affects their ability to deliver safe, effective quality care.

Through the 1990s and into the 2000s it became increasingly clear that the erosion of nurses' professional autonomy and control of practice made it ever more difficult to address workload issues.

But the staffing and workload language in the Nurses' Bargaining Association collective agreement today is the result of years of intense and relentless efforts by BCNU members and elected leaders to address the problem in a meaningful way.

The province-wide hospital nurses' strike of 1989 was a major milestone in the BCNU's mission to address workload.

"Today, nurses have the tools to truly make a difference."

- Debra McPherson

Nurses emerged from that round of bargaining with the Professional Responsibility clause as a way to document and seek redress for situations threatening patient safety and undermining nurses' ability to meet their professional standards.

Professional responsibility forms (PRFs) became a key tool to highlight workload problems and occasionally secure solutions. But the process had always been challenged by the fact it is not enforceable. All too often, employers cite budget issues as the reason they can't improve staffing or maintain negotiated improvements for more than one or two budget cycles.

In the mid-1990s BCNU's education department helped organize a series of grassroots workload campaigns. Members in designated worksites developed new techniques for documenting excessive work demands, appealed for more staffing and learned effective forms of advocacy. The campaigns achieved some success, convincing management to adjust staffing here and there, and helped train up new teams of activists on the issue.

During that period the union became increasingly influenced and inspired by the perspective and tactics of the California Nurses' Association which had begun its long political campaign for nurse-patient ratios.

Workload was the major issue during the 1998 round of provincial bargaining and the BCNU bargaining committee's top priority was mandatory ratios of registered nurses to residents in long-term care. The employers were adamantly opposed, and the NDP government of the time responded by proposing a $60-million fund to create about 1,000 new nursing positions around the province.

Unfortunately, the health employers' association insisted the new positions be allocated throughout the system, rather than targeting them in high priority areas. Many BCNU members reported they hardly noticed a difference.

BC's nurse staffing challenges were also compounded by the fact that other provinces and jurisdictions were wooing BC nurses with better wages and benefits.

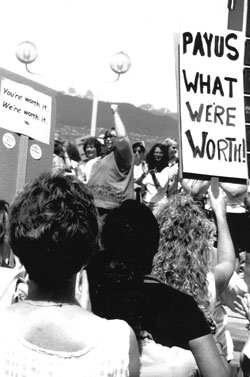

In 2001 nurses publicized their demands for a big wage increase by holding rallies, lobbying politicians, speaking out on radio talk shows, writing letters to editors, leafleting and running a successful, award-winning TV ad with the punch line "Sir, why don't we just pay them what they're worth?" Members collected over 85,000 signatures on petitions that called for "dignity, respect and fair pay for BC's nurses." The petitions were delivered to NDP Premier Ujjal Dosanjh.

Employers opened negotiations with 37 concession demands and no monetary offer.

Nurses held a massive rally on the lawn of the legislature in Victoria. With a provincial election looming, Premier Dosanjh and Opposition Leader Gordon Campbell both spoke at the event. Two days later, over 18,000 nurses voted 95 percent in favour of taking job action, which included an overtime ban.

The ban's success forced employers to table their first monetary offer, which nurses rejected. The government then appointed Vince Ready as Industrial Inquiry Commissioner.

Cranbrook's Patt Shuttleworth served as BCNU's vice president between 2000 and 2004. She began her career as a BCNU activist in 1989, when she became a workplace steward. Shuttleworth also served members as an executive councillor, provincial lobby coordinator, member of BCNU's Provincial Job Action Committee and as an officer of the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions. She served as East Kootenay region council member from 2008 until her retirement in 2014.

"The 'just pay them what they're worth' campaign was a real eye-opening time for me," Shuttleworth recalls. "It was the way that Debra approached bargaining, because we asked for an outrageous amount of money and some of us were kind of horrified at the thought of doing that," she admits. "But you learn a lot about the process as it goes on, and how you got what you needed."

"Wages are a proxy for status," states McPherson. "Nurses always say at every new round of contract negotiations, 'I would forgo the wage increase it you can guarantee safe staffing and working conditions. But if you can't do that then just give me the money.' It's been the same with every contract. If you can't fix this working situation then at least give me some money."

"We were dug into that job action," says Shuttleworth. "I remember our overtime ban. The executive worked out of a war room in shifts. Managers would have to call in, and we would say whether or not we would approve overtime. You know, what's surprising to me that we've ended up where we are in nursing, given how much overtime was worked, even though we had to approve it."

During the provincial election that year, nurses turned up the heat on politicians. Just days before the vote, Premier Dosanjh instructed a reluctant health employers' association to offer a wage and benefit package similar to the Alberta nurses' contract. Shortly after the BC Liberals swept into power, 20,500 members voted on the offer; 96 percent voted to reject the deal.

The Liberals moved quickly to impose a "cooling off period," forcing BCNU to abandon our overtime ban.

Nurses continued to pressure the new government to improve its offer, but in August the Campbell Liberals imposed it by legislation. The contract did, however, deliver wage increases of 25 percent over three years, bringing the top wage for point-of-care nurses from just under $50,000 annually to $62,000 per year.

In 2006 workload and patient safety were again at the top of the bargaining agenda. Polling showed members' top priorities were both a wage increase and measures to address workload and improve practice conditions. But when they were asked to choose between the two – they overwhelmingly chose workload and practice solutions over wages.

The 2006-10 contract did provide a significant wage increase; it also included an elaborate series of processes to address workload and practice conditions. Joint union-management workload committees would meet regularly at the regional and provincial level to examine problems and propose solutions, while strategic workload assessment teams (SWATs) would investigate the most immediate crises.

A series of workload demonstration projects piloted a variety of solutions, with the nurse-driven Synergy Model for a workload and acuity measurement tool emerging as the union's preferred option.

The 2009 bargaining sessions that extended the contract another two years to 2012 added the Joint Quality Worklife Committee as a top-level structure where the union would collaborate with senior health authority and government officials on solutions.

Again, budget issues intervened to undermine progress, particularly after the 2008 global financial crisis. Employers preferred "lean" cost-cutting schemes or workplace restructuring packaged up with names like "Care Delivery Model Redesign" where regulated nurses were replaced by unlicensed workers.

The independent assessment committees that were added to the PRF process in the 2006 contract produced some helpful recommendations. But in many cases budget concerns made long-term implementation problematic.

BCNU responded by putting safe patient care through safe staffing at the top of the NBA bargaining agenda for 2012. Member surveys showed the highest level of discontent about workload ever recorded. And the worst problems were noted in hospital med.-surg. and emergency wards, in long-term care and among case managers in the community.

The surveys also revealed that a serious contributing factor to the workload problem was employers who refused to replace nurses who were off from scheduled shifts. Often the reason was budgetary, with employers coming up with various policies against back-fill such as "never replace the first sick call."

The union's bargaining strategy involved achieving many of the benefits of nurse-patient ratios by negotiating mandatory workload language that required employers to respect and recognize the professional judgment of nurses to know what's best for patients.

Nurses moved closer to that goal with the breakthrough staffing and workload language in the 2012-2014 NBA collective agreement. The contract had clear, enforceable language to reduce workload and improve patient care with provisions that recognized and respected the clinical judgment of nurses. And for the first time ever, the contract required acute and long-term care employers to replace nurses off on leave from a scheduled shift, unless there were clear extenuating circumstances determined jointly by the nurse in charge and the manager. In the community employers were required to backfill at least the first two weeks of nurses' vacations.

Unfortunately, many health administrators in system were unwilling to adhere to the terms of the contract and, despite many nurses' best efforts, continued their refusal to replace nurses when required. Members responded by filing thousands of grievances, which ultimately led to a historic provincial staffing grievance settlement reached in 2015 and an arbitrated 2016 staffing settlement that compelled employers to follow through on their staffing commitments.

The 2014-19 NBA collective agreement that was ratified in 2016 built on the historic workload and staffing language contained in the previous contract and addressed the "compliance gap" with new joint processes to sort out just how many nurses remained to be hired to meet the previous contract's commitment to increase RN/RPN hours by 2,125 full-time equivalent positions over the next four years.

Employers also acknowledged nurses' call for a comprehensive health human resource management framework, while the health ministry committed to better achieve critical health service delivery objectives that included hiring more nurses.

The 2014-19 contract also saw each health authority establish a Nurse Relations Committee composed of union representatives and local employers who would meet bi-weekly and work collaboratively to address nurse staffing and general labour relations issues.

At the provincial level a new Nurse Staffing Secretariat Steering Committee and Staffing Oversight and Arbitration panel were created to work with health employers and set annual targets for compliance with negotiated workload and staffing language, and ensure they had "time specific strategies and budgets in place to meet compliance targets."

The current 2019-22 NBA provincial collective agreement has taken BCNU's push for safe staffing a step further. We learned from previous negotiations that, despite our best efforts to relieve staffing and workload pressure, the contract language lacked specific consequences for managers who fail to replace nurses when short-staffed, nor did it compensate those nurses left bearing the cost of additional workload.

Now, a nurse-driven staffing and workload assessment process has been negotiated that's designed to better ensure short-term staffing needs are met. The recently developed patient care assessment process (PCAP) allows point-of-care nurses to identify when additional nursing staff is needed, such as when units are below baseline or have identified workload. And if point-of-care nurses don't agree with managers' staffing decisions, they can grieve and may be eligible for a working short premium.

The working short premium is an important tool that changes the nurse-management relationship and allows nurses and managers to work together to address a common challenge. The goal is to align nurses' and managers' interests – nurses want enough staff to meet patient care needs and managers want to avoid paying an expensive premium.

McPherson is quick to stress the importance of the 2012-14 contract language and its refinement during subsequent rounds of bargaining. "We accomplished something unprecedented. Today, nurses have the tools to truly make a difference, to improve workloads and provide quality care," she says.

And today, as then, it's up to BCNU members with the support of the stewards, leadership and staff to make sure the language is used to make a difference for nurses and their patients.

A DECADE OF TURMOIL

The 2000s was difficult decade for health-care workers and all working families after the election of the BC Liberals in 2001. That year ushered in 16 years of attacks on unions and a privatization agenda that's had devastating impacts on the public services unionized workers provide and the people who rely on them.

But the turmoil of the decade also resulted in the eventual unification of almost all nurses into one union: BCNU.

Despite Liberal leader Gordon Campbell's campaign trail assurances that his government would cooperate with unions and honour negotiated contracts, the new premier performed a craven about-face once elected and rammed Bill 29 through the Legislature at the beginning of 2002.

The law gave the BC Liberals sweeping powers to rip up signed collective agreements, fire 10,000 workers – mostly women – without cause, and cut wages for thousands of other caregivers. It also stripped care aides and non-clinical health-care employees of protections and rights available to other workers under the BC Labour Code.

The new legislation served as the blueprint for the wholesale privatization of important health-care services while the Liberals held power in the province. It also opened the door for private health-care facilities to contract out services and eliminate union succession rights, which required health-care facilities to honour the former collective agreement negotiated with the previous contractor.

In response to the attack, BCNU and other public-sector unions launched a lawsuit claiming that Bill 29 violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms with respect to freedom of expression, freedom of association and equality rights for women.

The Supreme Court of Canada agreed, and in a legal rebuke of the BC Liberal government it ruled in 2007 that provisions in Bill 29 interfered with the right to bargain collectively and had indeed violated the Charter.

But the damage was done.

The government had already used the unconstitutional provisions to contract out nursing jobs, particularly in long-term care where BCNU members lost their wage rates, contract rights and pensions. Especially hard hit were health-care support workers. HEU and other members of the Facilities Bargaining Association (FBA) lost up to 10,000 jobs through contracting out to low-wage employers.

"BCNU is the work of several generations of nurses."

- Debra McPherson

The legacy of Bill 29 remains, as large parts of the long-term care sector and acute care support services – such as cleaning, food and laundry – remain privatized and owned by large foreign multinational corporations.

The legislation was only repealed by John Horgan's BC NDP government in 2018. While the move does not end privatization, it is a positive step that will end rampant contract-flipping in health care, and make for more stable care – especially for seniors.

If Bill 29 was a hard hit for workers in the FBA, conditions were made even worse with the Campbell Liberal's demand that unions in the association accept a 15 percent wage cut in 2004. The dispute had pushed the province to the brink of a general strike.

BCNU and most other unions were poised to throw up picket lines across the province before an 11th-hour deal was reached. It included the 15 percent rollback, which hit LPNs especially hard.

"Many LPNs in HEU felt that their concerns were not being addressed either at conventions or the leadership table," says McPherson. "And that had been brewing for some time, because I would get letters and phone calls quite regularly from HEU LPN members saying, 'come and get us please, we want out.' And BCNU had been resisting and resisting."

At the same time, some health employers were taking advantage of the fact that nurses were in separate unions to play them against each other. "In the 2000s the employer started to tinker with what our work was, and started saying, 'okay, this work that is being done by RNs could be done by LPNs, and this work that's being done by LPNs could be done by care aides,'" explains McPherson.

"It occurred to me that we had so much in common," she says. "And then finally it came to a point where it felt like it was in BCNU's interest and interest of all nurses – both LPNs and RNs – for us to be in one union fighting together for nursing."

In May 2009, BCNU launched an associate membership program to build relationships with all BC health-care employees and give LPNs the opportunity to see if BCNU was the right union for them on a permanent basis.

By September of that year, thousands of health-care employees had enrolled as BCNU associates and more than 2,000 were LPNs represented by other unions. The largest single group was LPNs represented by HEU. Response from this group was so strong that BCNU welcomed LPNs to full membership.

A two-year LPN-driven "Nurse + Nurse" organizing drive then ensued. It was resisted by the FBA unions that represented LPNs.

In 2012, after determining that a majority of BC's LPNs had signed BCNU representation cards, the BC Labour Relations Board ordered union representation votes for approximately 7,200 LPNs directly employed by five health authorities and Providence Health Care, and mailed ballots to eligible LPNs.

More than 5,000 LPNs, about 70 percent of eligible voters, cast ballots to decide their future union representation, and on October 11, 2012, the Labour Relations Board certified BCNU as LPNs' new union.

But legislative amendments were also required to finalize the merger.

A determined nurses' campaign followed, which involved petitions, postcards, emails and phone calls from many members – including RNs and RPNs as well as LPNs – to convince the provincial government to pass Bill 18.

The law, which was passed in April 2013, covered the 7,200 LPNs who voted decisively to join BCNU the previous year.

Bill 18 expanded the definition of nurse to include LPNs. It enabled LPNs to negotiate alongside other professional nurses in the NBA and be part of the provincial nurses' contract.

"This final step in the merger process was designed to make things smooth, seamless and efficient in discussions with health employers," says McPherson. "It put all nurses under the same umbrella to enable us all – licensed practical nurses, registered nurses and registered psychiatric nurses – to collaborate on ways to provide quality patient care."

More nursing history was made the following year when a majority of members in the Union of Psychiatric Nurses – a long-time NBA-affiliate of BCNU – voted to merge with our union in October 2014.

The UPN members' decision brought 1,100 RPNs into BCNU. Under the merger agreement, 16 mental health positions were created on BCNU regional executive committees.

The 2000s also saw greater recognition of the role of students, our retirees and members on long-term disability.

About 150 young nurses and students attended BCNU's first Young Nurses Conference in 2003. Participants learned about BCNU, talked about their experiences and discussed their concerns about the future of nursing.

Our union deepened its connection with student nurses and future members when in 2009 it created the BCNU Student Liaison program, which supports student activists in their role as a communication link between the students in class and BCNU.

In 2011 BCNU was instrumental in developing the Employed Student Nurse program in collaboration with the regulatory college. The successful initiative has created working opportunities for students in the health authorities and supports nursing graduates to become job-ready.

The NBA-health employer negotiation of the 2006-2010 provincial collective agreement saw the establishment of the Retiree Benefit Fund (RBF) that's designed to allow for the improvement of the inflation protection of nurses' pensions and enhanced retiree benefits.

Funded with nurses' 2008 one percent market wage adjustment, the fund is able to provide inflation protection and benefits for retirees who are NBA members. From 2009 to 2018, the Retiree Benefit Program used some of the money employers contribute to the RBF to reimburse a portion of the MSP premiums retired nurses had to pay.

"BCNU is the work of several generations of nurses, and the continued strength of BCNU depends on the important role they all play," says McPherson. "We owe it to all those activists, and to ourselves, to keep the vision vital and moving forward. Future generations depend on it."

DEFENDING MEDICARE

Since its inception, BCNU has been an ardent promoter of publicly funded universal health care. Nurses know firsthand that private care is bad for patients and health-care workers.

So, when private, for-profit medical and surgical clinics began setting up shop in BC in the early 2000s, our union called for enforcement of public health-care laws that are in place to protect patients from being charged unlawful fees when accessing necessary health care, and to prevent for-profit clinics from flouting the law.

It was during this period that BCNU began ringing alarm bells about clinics’ increasing violations of the Canada Health Act. The union began holding Premier Gordon Campbell’s BC Liberal government of to account for its unwillingness to enforce laws designed to ensure that care is provided on the basis of need and not simply the ability to pay.

BCNU also advocated for individual patients who were forced to pay out-of-pocket for medically necessary care, and we did battle in the arena of public opinion against for-profit health-care promoter Dr. Brian Day, the owner of Vancouvers Cambie Surgery Centre and largest private hospital in the country.

The union supported these patients as trial intervenors when Cambie launched a Charter challenge in 2009. Day and others were seeking have medicare, BC’s public health laws, struck down as unconstitutional.

Our union stuck by the patients in the years that followed, and we celebrated with them in victory after the BC Supreme Court issued a 2020 decision upholding important public health-care laws that protect patients from paying out-of-pocket for medically necessary health care.

The decision marked the close of a five-year long trial slowed by years of delays. But it meant that for-profit health care promoters ultimately failed to provide the evidence they needed to show how the expanded presence of private medical clinics would improve the health of Canadians.

A LEADER IN HARM REDUCTION PROMOTION

Nurses know harm reduction is a legitimate primary health care service that saves lives. And for the past 20 years BCNU has defended and promoted access to it.

The union provided financial support to help with the production of the 2002 documentary Fix: The Story of an Addicted City, which followed people who use drugs in the Downtown Eastside in their fight to open North America's first safe injection site. The film helped to raise awareness about the effectiveness of harm reduction, which led to the opening of Insite on East Hastings Street a year later.

After the federal Conservatives were elected in 2006, BCNU took on a high-profile role in the courts in order to protect Insite from the government's efforts to shut it down. The union argued that Ottawa's position violated the Charter of Rights and Freedoms by seeking to stop nurses from performing lawful work in a provincially sanctioned health-care facility and ensuring its clients stay safe and don't fall victim to injection drug poisoning that can be fatal.

BCNU's legal support helped ensure the 2011 landmark Supreme Court decision upholding Insite's right to continue operating. The justices' 9-0 decision ordered the federal government to abandon its attempts to close the facility.

Later, in 2015, BCNU spoke out against the federal government's attempt to stymie harm reduction with the passing of Bill C-2, the Respect for Communities Act that made all but impossible for new supervised consumption sites to open in Canada. Bill C-2 subsequently was repealed by the Trudeau Liberals – a move the union applauded.

BCNU continues to support harm reduction strategies as an effective nursing practice that saves lives. Today, the union has joined with advocates in calling for increased investments in harm reduction services like safe consumption sites, better access to safe supply such as prescribed pharmaceutical alternatives, province-wide investments in mental health, treatment and recovery services, and ending the criminalization of people who use drugs.

Our union continues to call on Ottawa to declare the current opioid and fentanyl poisoning crisis a National Public Health Emergency under the Emergencies Act. This action would unlock federal funding for evidence-based treatment programs such as the innovative program at Vancouver's Crosstown clinic that provides access to safe opioids like prescription heroin for those most at risk for overdose and poisoning.

In the meantime, BCNU will continue the fight to reduce and eliminate preventable deaths and support the thousands of individuals and families who have been touched by the opioid crisis.

STANDING UP FOR SENIORS

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the shambolic state of seniors' care in BC, nurses working in home health care, assisted living and long-term care have been calling for solutions to address the crisis.

The sector is a critical part of BC's public health-care system. Yet seniors today have less access to these services than they did in 2001. For the past 20 years, underfunding, privatization and fragmentation of the system have left many seniors, their families and communities patching together care – or even going without.

During this time BCNU has been advocating for solutions to improve seniors' care in the province.

In 2008, Vancouver Island's Cowichan Lodge became a flashpoint when Island Health (IH) shocked residents by announcing – without warning or consultation – the closure of 350 publicly funded and operated long-term care beds at the lodge and six other facilities.

IH wanted to force the vulnerable seniors occupying those beds to transfer into care homes operated by private, profit-driven companies that had secured big contracts with the health authority.

"The closures have nothing to do with improving care," said McPherson, who was BCNU president at the time, "and everything to do with delivering financial commitments and vast amounts of scarce public health dollars to the operators of these new facilities who have lucrative contracts with IH."

There is no question that more investments in publicly funded seniors' care is needed just on account of an aging population and increasing life expectancy. However, between 2001 and 2016, access to long-term care and assisted living spaces actually declined by 20 percent. And BC's seniors today have less access to publicly funded home support today than they did in 2001.

Strengthening the system of home and community care in BC will require stopping the privatization of the home and community care system, improving access to publicly funded home and community care services provided by health authorities and non-profit organizations and developing a specific framework and action plan to improve access and service integration.

Today, our union's seniors strategy working group consults with members who work in the sector and helps lobby governments for desperately needed action and investment.

KEEPING MEMBERS SAFE

Members' occupational health and safety has been an area of growing scope and importance since our union's founding 40 years ago. Today, BCNU's OHS department supports members with a range of services, from health and safety education and training, to WorkSafeBC advocacy, disability management, and long-term disability support.

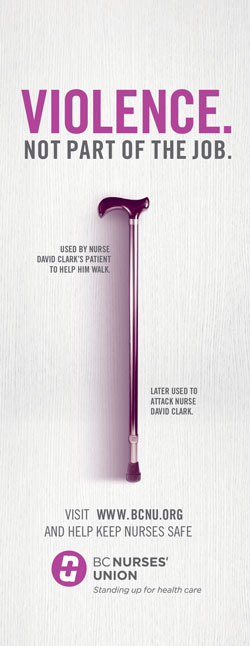

Members today are also aware of their OHS rights and understand that dangers, such as violence in the workplace, are not part of the job. It wasn't always this way.

"I can remember being hit and spit at and all that sort of stuff," says Pipe of her early years on the job. "When I first started violence was the silent plague of nursing. Now it's open and being discussed and we're building on that.

"When I first started violence was the silent plague of nursing."

- Linda Pipe

"When I was on council, we encouraged staff and stewards to make workplace violence a top priority – and especially make sure the public was more aware of it," she says.

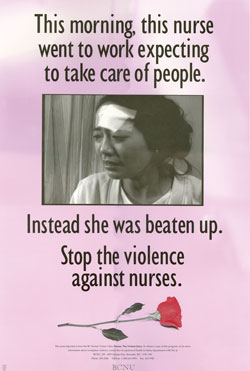

In 1992 BCNU launched a highly successful anti-violence campaign, with a video, literature and media blitz. "We engaged the public and our employers in a dialogue about the issue," recalls McPherson. "Much progress has been made over the past 30 years, but employers have not taken seriously enough the real dangerous situations that nurses often work in – and that's why it's still a problem for nurses today."

Since that first provincial campaign, the union has run several public awareness initiatives. Our most recent violence-prevention campaign was launched in 2017 to sound the alarm about the fact that the number of violent incidents in BC had climbed significantly over the previous decade despite nurses' calls for employer action.

Award-winning TV-ads drove the message home and the union set up a 24-7 violence support hotline with access to trained trauma counsellors and support for nurses who had been assaulted while delivering care.

The union gathered commitments from politicians and candidates during the 2017 provincial election and in 2018 BCNU leaders delivered 25,000 signed postcards to the provincial legislature to show strong public support for violence prevention measures in health care. These included better training for security personnel, the building of a provincial system to track violent patients, tougher sentences for those who criminally assault nurses and better WorkSafeBC support for nurses impacted by violence or other workplace traumas.

Today, occupational health and safety leaders are also focused on developing the kinds of standards for psychological health that are already in place for the protection of physical health.

A major milestone in this area was reached in 2016 when BCNU successfully negotiated the Canadian National Standard on Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace into the NBA provincial contract.

The Standard is the first of its kind in the world. Developed by the Canadian Standards Association (CSA Group), it is a voluntary set of guidelines focused on the development of a system of positive factors that support psychologically healthy and safe workplaces.

The push to develop the Standard came from the growing recognition that mental health problems and illnesses are the leading cause of short- and long-term disability in Canada. The toll on Canadian workers and workplaces is substantial, and nurses and health-care workplaces top the list in numbers of claims. However, there had been no comprehensive national standard to help guide organizations that wanted to take action.

BCNU is the first union in Canada to have successfully negotiated the Standard into a collective agreement. As NBA contract language, it is intended to supplement the other tools that nurses have to address their working conditions, such as grievance filing and using the professional responsibility process. But what makes the Standard unique is its focus on workplace culture and the behavioral factors at play that also have a significant effect on nurses' working conditions.

When nurses do suffer mental injury, they too often endure further trauma through the WorkSafeBC reporting process. In 2016, BCNU began our campaign for mental injury presumption status for nurses.

After rallying and lobbying for over a year, BCNU activists and leaders convinced the provincial government to add nursing to the list of occupations that now have easier access to workers' compensation for mental-health disorders that come from work-related trauma.

The win means members who have been living with mental injuries including, but not limited to, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of workplace trauma, will now have access to services and compensation.

Today, BCNU has made mental health supports for members one of its highest priorities.

Dedicated mental health advocates now sit at BCNU regional executive tables. The Enhanced Disability Management Program first negotiated with employers in 2010 continues to support members suffering from an occupational or non-occupational illness or injury.

The union's Licensing, Education, Advocacy and Practice program is also an invaluable service for those needing assistance with practice, mental health, addiction and other issues.

And for the past five years, BCNU has been offering personal resilience education designed to help nurses identify things like compassion fatigue and signs of post-traumatic stress disorder in themselves and their colleagues.

ACHIEVING INCLUSIVITY: THE CHALLENGE WE FACE TODAY

BCNU's history has been a story of bringing all members together to face our shared challenges and achieve the fairness and respect we would not be able to attain individually.

But our work is far from over. Despite the progress that's been made, our organization is in many ways a reflection of the society of which it is a part. That means we need to be aware of the ways that racism and discrimination are present in our union and work to make space for marginalized members.

Knowing our past gives us an understanding how far we still have to go.

"In the 80s it was really slow," says McPherson. "Our little group of about nine people brought numerous resolutions to convention about pay equity or reproductive rights and we would just get booed off the floor. Sometimes it was awful what we endured at some of those meetings. And we lost people. I remember we brought a resolution to convention about recognizing gay rights and they refused to debate it. That year we lost two stewards because they said, "We're not wanted here so we're leaving," she recounts.

"Trying to build awareness of social justice issues was really hard fought and it didn't come easy. It involved bringing resolutions again and again and again or else risk losing people who felt they didn't have a place in the union because they couldn't get their voice heard."

Stories like McPherson's can help us appreciate why BCNU's human rights and equity initiatives over the past 15 years have been so important for achieving the true unity we desire. The essence of human rights and equity work is inclusivity. It's about broadening our frames of reference and considering how we look at issues in our workplaces and communities, and in our union, and asking ourselves, "who is included and how?"

So much of this work can be credited to Mabel Tung.

Tung served as BCNU's provincial treasurer from 2006 until her retirement in 2016. She immigrated to Canada after graduating from nursing school in Hong Kong in 1979 and began caring for patients on a Vancouver General Hospital (VGH) medical unit in 1981.

Tung says she was unaware of the union, and not interested in activism at the beginning of her career. That changed with the events in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989. She remembers crying while watching television news coverage of soldiers killing students and other democracy advocates.

Until then she had never considered herself to be a particularly political person. But the innocent blood that was spilled changed the way she viewed the world. "Tiananmen Square really woke me up," recalls Tung, who joined hundreds of other protestors outside Vancouver's Chinese consulate as word of the massacre spread around the globe.

"We wanted to project BCNU as a union that really cares about people and human rights."

- Mabel Tung

After that deadly day, the soft-spoken RN transformed herself into an outspoken community advocate and union activist.

Tung first got involved with BCNU during the strike of 1989 and became Central Vancouver's regional treasurer before her election to the union's Provincial Executive Committee.

She played a leading role in the establishment of BCNU's Multicultural Group and Indigenous Leadership Circle in 2005, and the Human Rights and Diversity Committee in 2007.

Tung was also one of the key architects of BCNU's human rights and equity caucuses. Today, the caucuses work to enhance the voice and place of members who have experienced historic and systemic discrimination and marginalization. They were established according to the principles of the BC Human Rights Code and recognize the need to support members who may feel less welcome and find participation more difficult by giving them a space to speak freely about issues that matter to them.

Tung says it was McPherson who inspired her to embark on her leadership path. "Debra taught me about union principles, human rights and equity issues, justice among people and how to treat everybody fairly and equally," she recalls.

"She's the only one who encouraged me to run for provincial treasurer, otherwise I would have never put my name up there," Tung says. "I saw that the provincial executive had no colour, and thought, as a Chinese person from a visible minority, I probably shouldn't be there and that I may not be good enough. So, the experience really changed my life."

Tung recalls a moment of insight while attending BCNU convention in 1998.

"I was amazed to see so many brave people on the convention floor speaking at the mic and voicing their concerns about nurses' issues. But one thing that really struck me was the fact that the room was so white, because I knew a lot of nurses at VGH were Filipino or members of other visible minorities," she says. "And at each region's table there were only one or two people of colour as delegates. So, I kind of questioned that and saw that it was not really representative of the union's membership."

It took Tung another seven years to translate her experience and concerns into a viable plan of action. "It's important to know that I didn't want to rock the boat at that time because I understood that a lot of people didn't think that it was necessary to start something so particular. They said, 'I don't see any colour.'

"And I still remember that. They didn't think a multicultural group was necessary because they said, 'everybody's equal.' So that's why I first started a group that could bring everybody in who felt they were different or 'the other.'"

The Multicultural Group was short-lived, however. "After a while, we found that if we were to do it right, we would need to create a number of caucuses to address the specific needs of members and founded on their identity and lived experience," Tung explains.

Her vision of how the union might better represent the diversity of our membership was founded on the premise that not only is it possible to be "unified without uniformity" but that equity-seeking groups within unions actually energize the labour movement by bringing more people into its activist cadre.

Today four equity-seeking groups (Indigenous Leadership Circle, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer Caucus, Mosaic of Colour, Workers with Disabilities Caucus) and two non-equity seeking groups (Men in Nursing, Young Nurses Network) function under the auspices of the BCNU's Human Rights and Equity Committee.

Caucus members often identify with more than one caucus, and they frequently seek opportunities to productively engage with each other out of a profound and sympathetic commitment to justice and equity.

When the Workers with Disabilities caucus initiated its campaign to ensure that BCNU spaces and events were scent and fragrance-free (because the presence of these smells was a barrier to participation for many members) the work was supported by all of the caucuses. There was an implicit recognition that the debilitating effects of exposure to a fragrance could affect anyone – and not only someone who explicitly identifies with this caucus.

The cross-caucus discussions that take place when a problem like this is brought forward offers members an opportunity to reflect on the intersectional dimensions of this experience for those whose identity may be informed by issues of gender and race/racialization in addition to their disability.

For Tung, this ongoing project of thinking with and about the complex challenges of discrimination and how best to address them animated her initial vision of human rights and equity.

"We wanted to project BCNU not just as any union, but as one of the unions that really cares about people and human rights, and that discrimination is one of those things our union should pay attention to," she explains.

Since the establishment of the Multicultural Group in 2005, BCNU has continued to listen to the experiences of discrimination members have faced. Much has been achieved, but more remains to be done.

Nurses and health-care workers who might identify as bisexual/lesbian/gay, or who are non-binary, and nurses and health-care workers who are trans, continue to experience appalling levels of discrimination and violence.

Nurses of colour and Black nurses, in particular, continue to be subjected to multiple forms of racialization and racial violence.

Disabled workers continue to face systemic ableism in their workplace and their communities while also having to contend with the causal cruelty of their colleagues.

And Indigenous nurses and health-care workers continue to face multiple forms of discrimination founded on an ongoing process of colonization – as the 2020 report, In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care, made abundantly clear.

It was a devastating indictment of our health-care system. But for the members of BCNU's Indigenous Leadership Circle, the report merely confirmed their everyday experiences. Indeed, they have been speaking up about these issues since 2005, when the circle was first established.

The In Plain Sight report advances a set of recommendations for addressing anti-Indigenous racism founded on the principles of decolonization, anti-racism and cultural safety: a blueprint for a more just and equitable health-care system.

These principles offer us a road map for the next 40 years of union activism as we strive to create a decolonized, anti-racist and culturally safe organization that's alive to the nuances of our identities and our lived experiences, and of how power operates through our organization, our workplaces and communities, and what new forms of imagination are required for us to conceptualize a place and spaces where we all feel we belong.

The project of reimagining BCNU's future has already begun through our annual human rights and equity conference. The event brings together a diverse and inclusive cross-section of our membership – including many young and new nurses – and offers us time and space to critically reflect on what is needed to remake our union, our communities, and our world.

"The conference started off as a way to "celebrate Human Rights Day on December 10 and take the opportunity to educate members about human rights and the diversity of the membership," Tung explains. But over the years she says it has also become a place for members to gather and dialogue with each other about who we are and who and what we would like to become.

"I'd like to see more young nurses make BCNU an important piece of their lives."

- Patt Shuttleworth

Since 2008, the event has facilitated in-depth conversations on a range of issues, from the climate crisis, what a post-pandemic world might look like, the many meanings of home in the midst of the continued dispossession of Indigenous peoples, how to be an ally to each other in our collective struggle for justice and equity, to articulating a vision for a genuine and just process of truth and reconciliation.

BCNU's human rights and equity initiative can be understood as a necessary corrective to a history of unionism that, while achieving gains for some, also systematically excluded others.

Our province has come a long way since the Asiatic Exclusion League led a white supremacist mob through the streets of Vancouver in 1907, but the spectres of those sentiments continue to haunt our current moment – as the upsurge in anti-Asian racism and violence in the past months have sadly reminded us.

This is our work. This what needs to be done. And this is what BCNU is committed to as we look to the future.

BUILDING OUR FUTURE

How can we build and strengthen our collective effort and make sure BCNU will be here in another 40 years?

Pipe says working nurses today should never forget that knowledge is power. "Know your contract, and if you have questions, know who to contact to get that information and fight for your rights," she advises. "Don't acquiesce to what a manager says you can or cannot do. Question it."

Perspective is important too, she says. "Even if we don't get everything we aim for today, it's important to build on small successes – and don't just think of yourself; think of what you can do to make things better for that future nurse."

And the rewards are many.

"I really enjoyed my time with the union," says Shuttleworth. "It taught me so much that I would never have learned if I had just continued working and didn't get involved. That was a really important piece of my life and I'd like to see more young nurses make it an important piece of their lives."

Ducharme agrees. "I wanted to be a nurse since I was three years old sitting under the Christmas tree in my nurse's cap and apron that my mom made me," she says. "It was a life career, and I would still strongly recommend it."

But she stresses that her professional life would have been much different without a union. "I was working seven days in a row when I started," Ducharme reports.

"It's important for members to know that the employer never voluntarily gave us a dental plan or extended health benefits or vacation and sick time. Every one of those things were negotiated and fought for by the union to support our members. I can't image our working environment if the union hadn't negotiated those and other things."

McPherson says it's about ensuring there is a place for each and every member in our union.

"I go back to my lesson that I learned in 1981. The union is a place for you to find your voice and to stand up for your rights," she states. "And it's my hope that BCNU will continue to successfully provide that support – today and in another 40 years from now."

If the proverb holds true, BCNU will indeed be here as an organization of members supporting members on an often slow but unwavering journey together toward justice.

UPDATE (Summer/Fall 2021)

1981

BCNU is born at founding convention after vote to leave the labour relations division of the Registered Nurses Association of BC

Original BCNU logo

1980s

BCNU organizes campaigns to bring long term care nurses into the union with improved wages and conditions

Delegate book, wage and policy conference, 1981

1983

BCNU supports Operation Solidarity

1987

BCNU protests Bill Vander Zalm’s Bill 19 and 20

1988

The Licensing, Education, Advocacy, and Practice (LEAP) plan is established to assist members charged in relation to a job-related professional act

\

1989

First province-wide hospital strike results in 26% wage increase in over two years

1992

BCNU launches its first antiviolence campaign

1993

Employment Security Agreement reached with provincial government

1994

BCNU joins the National Federation of Nurses Unions (now CFNU).

Lower mainland community nurses fight and win long strike for wage parity

1996

Union achieves one provincial contract for all health sector nurses

1997

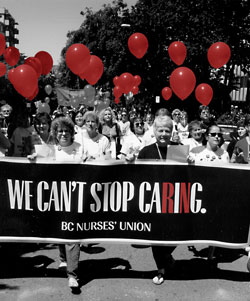

“We Can’t Stop Caring” campaign promotes the value of nurses

1998

BCNU builds and moves into 4060 Regent Street, Burnaby

2000

BCNU mounts nurse-led "Hurl, Hemorrage and Heal" theatre project

2001

Long job action results in 25% wage increase over 3 years

2002-2003

Union campaigns against BC Liberal government cuts

2002-2011

BCNU supports street nurses and harm reduction, culminating in Supreme Court victory for insite

2005

Human Rights and Diversity Committee established

2006

Union campaigns to protect and improve medicare

2007

Supreme Court victory strikes down Bill 29, provincial legislation that saw government tear up signed contracts

2008

BCNU negotiates funding for inaugural three-year nursing co-op program at BCIT

2009

BC Supreme Court victory overturns sections of Bill 42, a government gag law that sought to prevent advertising prior to provincial elections

2009-2012

After a long campaign, more than 7,000 LPNs vote to join BCNU, bringing membership to more than 40,000

2011

BCNU removes itself from CFNU but maintains a friendly relationship with other nursing unions and CFNU

2012

Nurses’ Bargaining Association negotiates a landmark collective agreement that gives nurses the tools to reduce heavy workload, improve patient care and adds more RN/RPN positions

2013

BCNU breaks ground on new expansion of provincial offices

Rebranded BCNU logo

2014

Union of Psychiatric RPNs across all sectors Nurses members vote to merge with BCNU

2015

BCNU’s Education Centre opens

Two-year campaign reverses Island Health’s Care Delivery Model Redesign scheme and restored 48,000 nursing hours in Nanaimo

2016

Members vote 85% in favour of the terms of the 2014-2019 NBA provincial contract that for the first time unites LPNs, RNs and RPNs across all sectors

2017

BCNU launches major violenceprevention campaign calling for trained worksite safety officers

2019

Nurses celebrate mental health injury legislation that makes it easier to access workers’ compensation

2020

Nurses celebrate BC Supreme Court decision upholding important public health-care laws that protects patients from out-of-pocket for medical expenses

2021

Today, BCNU represents more than 48,000 members, most of whom are covered by a single provincial contract.